Parviz JahedParviz Kimiavi is one of the most outstanding New Wave directors in Iran. I rewatched his documentaries and feature films as part of a research study on the Iranian New Wave cinema. While revisiting Kimiavi’s films, I started paying more attention to details and stumbled upon things that I had not realized before, such as the utopian aspect of his cinema, his approach to nativism, his critique of modernity, and the reflection of the “creative melancholy” that Iranian intellectuals display in both his documentaries and feature films. At the same time, I still believe that Kimiavi’s cinema is modern and avant-garde in terms of form and structure with an avant-gardism and aestheticism that is influenced by the avant-gardism of the European cinema, the French New Wave, and French surrealism.

I do not believe that Kimiavi’s documentaries are just a type of unobtrusive observational cinema, or what is often called the “fly on the wall” approach, but rather a cinema in which the director offers his opinion on the subjects by creating the reality in front of the camera and by editing. In other words, his cinema is closer to Dziga Vertov’s theory of Cine-Eye (or Kino-Eye), which refers to the camera capturing the important moments in life and the director using his creative editing to shape it into a more effective form.

Kimiavi’s interest in creative montage and interpretive documentaries can be seen in Godard avant-garde experiments in French cinema. His documentary films are not presenting absolute reality, despite their realistic and documentary aspects of life, but they are what John Grierson, the pioneering documentary maker and one of the leading figures of the British Documentary Film Movement, called a creative interpretation of reality. In Kimiavi’s view, an event or story in a documentary film is an ambiguous truth which one must try to understand while showing its multiple layers. He combines reality with imagination and links subjectivity with objectivity, which is what gives his cinema a poetic quality. This derives not only from the fancy but also the fluidity of space and use of a few surreal elements, like the collapse of the walls of the Arg-e Tabas in P Mesl-e Pelican (P Like Pelican) (1972) or the surreal scene in Bagh-e Sangi (The Garden of Stones) (1976) where Darvish Khan meets a mysterious creature. Kimiavi’s cinema is also symbolic and allegorical. The Garden of Golshan is a symbol representing heaven when Aseyed Ali Mirza opens its doors and enters it.

On the other hand, Kimiavi’s films can be considered postmodern because of their postmodern elements such as ambiguity, uncertainty, breaks in narratives and time, references to cinema and parodying of films, creating a distance between the audience and the world depicted, and their interpretive nature. The characters in Kimiavi’s films typically find themselves in situations where they cannot show immediate reactions and they come to a point which Gilles Deleuze calls the dissolution of the sensory-motor situations. According to Deleuze, the images that are fundamentally distinct from the sensory-motor situations of the action-image will turn into an optical and sound situation that is connected to virtual, mental, and mirror images.

As Deleuze pointed out “there is a necessary passage from the crisis of image-action to the pure optical-sound image…the optical and sound situation is, therefore, neither an index nor a sonsigns. There is a new breed of signs, opsigns and sonsigns. And clearly these new signs refer to very varied images- sometimes everyday banality, sometimes exceptional or limit-circumstances- but, above all, subjective images, memories of childhood, sound and visual dreams or fantasies, where the character does not act without seeing himself acting, complicit viewer of the role he himself is playing, in the style of fellini. (Deleuze, 4-6, 2005)

Therefore, if we look at Kimiavi’s films from a Deleuzean viewpoint and his time-image theory and pure optical-sound situation idea, then the logical and measurable time relations between the frames, as the important feature of the movement-image, give way to illogical and indeterminable relationships while opening doors to various interpretations. From this aspect, we can assign a postmodern quality to Kimiavi’s cinema in which there is no certainty, and almost all interpretations become possible. Therefore, this article is simply one interpretation of Kimiavi’s work with references to some signs and concepts in his films, which have no fixed, definite interpretation.

I have not seen the films that Kimiavi made outside of Iran, except for Blue Jeans (1984), The Trench (1981), and a few segments of À propos de Nice, la suite (1995), which is about a woman who claims that she played in Jean Vigo’s À propos de Nice (1930). This article therefore focuses on the films that he made in Iran before immigrating to France for the second time. Of course, he examines non-urban spaces (specifically, the woods) in The Trench, similar to his films made in Iran, and looking for an odd and unique French character. Jacque Bronto of The Trench is a man who has dedicated his whole life to keeping the memories of First World War soldiers alive. This attempt to preserve or revive values and concepts which are in danger of being forgotten forms the central ideology of Kimiavi’s films.

I believe that, besides their personal and subjective aspects, Kimiavi’s films show his critical approach towards modernity through their social aspects and they go hand in hand with the political and intellectual discourse of nativism and root-seeking tendencies which were prevalent in Iran in the 1960s and offer their critical view of the Western modernity that intellectuals such as Jalal Al-e-Ahmad and Ali Shariati were also criticizing. Kimiavi’s films are similar to the “Westoxification”(Gharbzadegi) discourse put forward by Al-e-Ahmad since one can feel in them the suffocating meaningless and emptiness of the society in transition to modernity. Nevertheless, Al-e Ahmad borrowed and developed his concept of “Westoxification” from Ahmad Fardid’s analysis of Martin Heidegger. As Ali Mirsepassi brought forward, Al-e-Ahmad and other anti-Western intellectuals of Iran in the 1960s were the opponents of “the Westerned-backed Pahlavi state of the Shah who was violently forced into being through a military coup in 1953 and terminated a decade of hopeful democratic experimentation. It was this above all that engendered a hatred for and mistrust of the “West” as such…” (Mirsepassi, 2010, p.119)

According to Ali Mirsepassi, there was a desire among the Iranian intellectuals to reconfigure modernity in the national context which is nativism in Mehrzad Boroujerdi’s analysis. (Mirsepassi, 2010, p.117)

Al-e Ahmad’s had a significant influence on the whole generation of Iranian intellectuals, writers, artists and filmmakers by offering a “nativist” ideology instead of the “universalist” ideology of the Iranian leftists which was a dominant discourse of the time. We also see Kimiavi under the influence of Al-e Ahmad’s anit-Western ideas in his films. Kimiavi like the character of the film director in Mogholha (The Mongols) (1973), played by Kimiavi himself, is trapped by the constraints of modern life. However, the difference between Kimiavi’s cinema and Al-e Ahmad’s “Westoxification” discourse is the fact that his critical approach, unlike Al-e-Ahmad’s or Shariati’s, does not get political and radical because his films do not attack the government and those in power but very similar to Dariush Shayegan or Ehsan Naraghi, he only resorts to examining the influences and the negative role of modernity and Western culture in Iran without turning his attention towards political power relations in Iran.

In his book Asia dar Barabar-e Gharb (Asia Facing the West), Dariush Shayegan criticizes Western modernity and expresses regret about the collapse of traditional civilizations. From this perspective, and in a different reading, it can be claimed that Kimiavi’s films were made with a utopian mindset. Although, to paraphrase what Peter Fitting had said, there is no accepted, fixed definition of “utopian cinema”, one can still reach a specific definition of the genre based on examples from documentaries and films available to us, and one can list the shared features between these films. Fitting defines “utopian cinema”, similar to “utopian literature”, as a work of art which talks about a non-existent world or a world from the past that no longer exists. This aspect of “utopian cinema” makes it a cinema of nostalgia that longs for the past and the disappearance of values.

When the villagers in Kimiavi’s OK, Mister! (1979) face the culture of the colonizers, represented by a semi-fictional character named Darcy (an outstanding performance by Farrokh Ghaffari), they forget not only their traditions and customs, but also their mother tongue and they start speaking gibberish. Peter Fitting has also referred to the representation of a simpler, happier world in “utopian films” as an alternative world for the sad and complex world in which we actually live. According to Fitting, “hope for a better life and for happiness in the world exists in utopian characters as they wait for a better future.” This means that utopian films like Lost Horizon (1937) are optimistic and offer salvation and a breaking free from the pain of the modern world, unlike “dystopian films” such as A Clockwork Orange (1971), 1984 (1984), Lord of the Flies (1963), Metropolis (1927), and Brazil (1985), all of which paint a bleak and pessimistic picture of the world in the future. Fitting believes that such films include not only science fiction films that create another world for us, always set in an unclear future, but can also include documentaries in which this non-existent world is discussed or shown, whether as a world that is long gone, or one that we should create.

In his documentary film Takht-e Jamshid (Persepolis,1960) Fereydoun Rahnema says “One of the reasons why I paid attention to Takht-e Jamshid was that the environment of Takht-e Jamshid and its ruins gave me the opportunity to express different ideas and thoughts about life and art […] Takht-e Jamshid is a ruin that was built thousands of years ago. We bring out imaginations and visions out of an objective reality […] cannot we talk again about the places that have been destroyed and ruined?” Rahnema’s goal with his television project Iran Zamin was to record subcultures, the remains of the lost civilization, and the glory of ancient Iran through an archeological and ethnographic approach. This goal was similar to the Disappearing World project, a British documentary television series produced by Granada Television in the early 1970s in which documentarians and ethnographers went to different communities and societies to record the cultures that were being forgotten and destroyed, a style of documentary- making which was pioneered by the great American documentarian Robert Flaherty.

After Rahnema started the Iran Zamin project for the research department of National Iranian Television in 1970, he invited young filmmakers such as Parviz Kimiavi, Nasser Taghvai, Mohammadreza Aslani, Manoochehr Asgari-Nasab, Manouchehr Tayab, Nasib Nasibi, and Houshang Azadivar and equipped them with cameras and gave them complete freedom to travel to different parts of Iran and record subcultures and what has left from the past. This became a series of exploratory, anthropological, and ethnographic documentaries of priceless historical and cultural significance. Among the directors Kimiavi, Aslani, and Taghvai followed a personal, subjective approach in their films, as opposed to other Iranian documentarists such as Manouchehr Tayyab, Manouchehr Tabari, or Gholamhossein Taheridoost, who followed an ethnographic and exploratory approach. For example, Kimiavi’s vision in Ya Zamen-e Ahoo (Oh Guardian of Deers,1970) and Tapeh-haye Qaytariyeh (The Hills of Qaytariyeh,1969) is not the vision of an archeologist or a traveler who is looking for ancient artifacts in the depths of the dirt or the viewpoint of a tourist who enters the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad.

Kimiavi’s films have a yearning to show the disappearance of cultures, characters, and lost or forgotten worlds that reflect the collective melancholy of intellectuals in 1960s Iran, the nativist discourse of the time, and the idea of going back to one’s roots and ideas of authenticity.

In his essay “Mourning and Melancholia” Freud makes a clear distinction between “mourning,” and “melancholia,”. He considers mourning as a standard process of grieving for a lost object, and “melancholia,” as a refusal to give up on the lost object. For Freud, Melancholia is linked to an unknown loss, a loss that doesn’t know itself. Giorgio Agamben takes the Freudian concept of melancholia and puts it in a larger historical-geographical context in order to explore the link between melancholia and the human existence. For Agamben, melancholy is a way of making connections with objects that are unreachable or even non-existent. Agamben emphasises on fetishism and its relation to melancholia when he describes: “the fetish confronts us with the paradox of an unattainable object that satisfies a human need precisely through its being unattainable. Insofar as it is a presence, the fetish object is in fact something concrete and tangible; but insofar as it is the presence of an absence, it is, at the same time, immaterial and intangible, because it alludes continuously beyond itself to something that can never really be possessed”.(Agamben, Stanzas, p.33)

The fetish objects contain experiences of loss and the melancholic mourning over this loss. One can follow Morad Farhadpour and Maziar Eslami’s Agambenian-Freudian reading in their book Paris-Tehran when they claim that the nativism and anti-colonial discourse is also a collective melancholy of Iranian intellectuals who are mourning for a glorious past and a golden age that has been looted throughout history. Accordingly, one can claim that the archeological tendencies of intellectuals such as Sadegh Hedayat and Fereydoun Rahnema and the anti-colonial root-seeking tendencies of thinkers such as Al-e-Ahmad and Shariati reflect this collective melancholy in different ways. They both defend a national and local identity that has been attacked by an outside culture. This invasive culture has an Arabic nature for Hedayat and a Western nature for Al-e-Ahmad and Rahnema but all of them have tried to revive or retrieve a genuine local identity.

Grievance over the disappearance of past glory, sadness for Ancient Iran, and the stolen legacy and cultural sources act as the “lost object” in Rahnema and Hedayat’s works, which show the same collective melancholy that appears in different forms in the works of Iranian writers and filmmakers of the 1960s and 1970s such as Kimiavi, Beyzai, Hatami, and Aslani. If we look at the works of these filmmakers from the angle of utopian cinema then we will find that all of these filmmakers were trying to revive an ideal utopian world even though they emphasized the disappearance and destruction of a once glorious world. Fitting believes that utopian films always contain a hope for a new world to be created from within the ruins of the old. In The Hills of Qaytariyeh the bones in the archeological site of Qaytariyeh belong to a world that no longer exists. The ruins of Arg-e Tabas collapse in this film and Aseyed Ali Mirza is its last guard. At the end of P Like Pelican there is another sign of this loss though, on the other hand, the film offers a hope for a better future world to rise out of the desert and the ruins of Tabas. In The Hills of Qaytariyeh the bones scream “swear on the sun that we will escape.” In Oh Guardian of Deers those who play Naqareh at the Imam Reza shrine promise cures to the ailing pilgrims who are waiting for a miracle at the shrine. The strange, fanatic dance of Darvish Khan in The Garden of Stones and how the way he hangs himself from a tree can be a sign of his escape from the present situation and his hope for all the unrealized hopes and dreams in this material world.

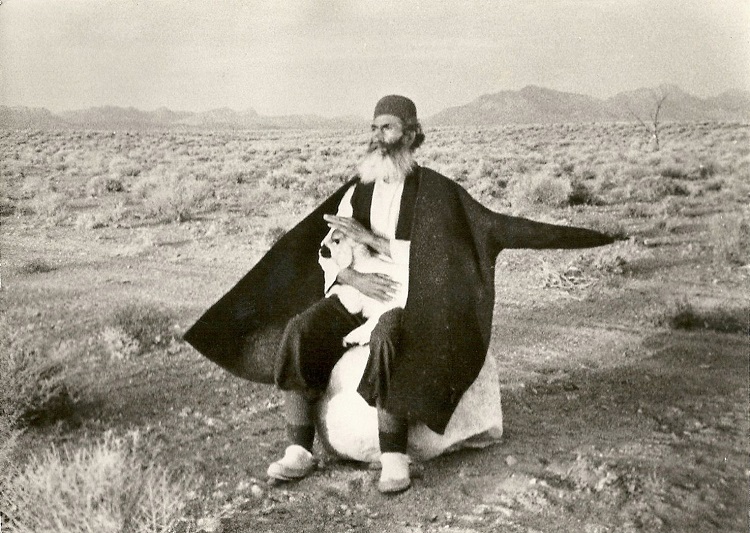

According to Fitting, in utopian films madness and schizophrenia are the representations of the individual’s attack against the social system, or an escape from the accepted norms in society – a utopian escape from a dystopian situation. Commenting on the unique characters in his films, Kimiavi says that “my characters are not unique, but the society has turned them aloof and strange.” In P Like Pelican, which is a cinematic poem about the madness of a rural mystic in the desert, Aseyed Ali Mirza has waited for a deity for 40 years in the ruins of Tabas. At the end of the film, his utopia appears in the form of a white pelican in the Garden of Golshan, which is the promised heaven, and he runs toward it in his white clothes. After entering the pool inside the garden, he becomes one and the same with his spiritual beloved, the pelican, and is saved from all of the pain and suffering in the world. In The Garden of Stones, the stone is a sign of the other world that only Darvish Khan, a deaf and mute shepherd living in the desert, can communicate with. The way the film begins, and the way that Darvish Khan encounters the rock which comes upon him like a godsend from the heavens, is similar to science fiction films. There is a secret in the perforated stones, and there is a wisdom in Darvish Khan’s stone garden that only he knows and that the audience never witnesses.

Kimiavi’s documentary and fiction films often imagine a place with its own natural order and rhythm that is threatened by unnatural and foreign elements such as technology. The simple, primitive, mystic world of Aseyed Ali Mirza in P Like Pelican is threatened by the people of Tabas and their children, who think of him as a madman. He is a deserted outsider who is alienated from the city and urban civilization, having lived in the ruins of Arg-e Tabas for 40 years without ever setting foot inside the city.

In The Hills of Qaytariyeh archeologists even unsettle the world of the dead and we hear the skulls in the dirt saying “Now the days of freedom in the kind heart of dirt are going to end, and this is the beginning of captivity.” In The Mongols the swarm of television officials rushing to the villages of Iran is as invasive and destructive as the decision by the governor and the cultural heritage officials of Kerman to take Darvish Khan’s stone garden in The Old Man and His Stone Garden (2004) so they can turn it into a tourist attraction. This destructive element in The Garden of Stones is shown in the form of technology or the disruption of village life by the forced recruitment of people into the military. If the invasion of Western culture in Iranian society is shown symbolically in The Mongols then it is presented more directly in O.K. Mister in the form of an oil-seeking Western colonizer William Knox D’Arcy. In this film, we also see how the locals in the village change and lose their identity after D’Arcy enters their lives and they encounter the swarm of Western culture and western products such as radios and television sets.

Nature and non-urban places play a significant role in Kimiavi’s films. Except for The Mongols and Iran Is My Homeland (1999), which feature a few urban scenes, Kimiavi’s usual locations are nature and rural areas. I believe that this turn to nature in his films is also another reflection of the nativist discourse of the 1960s in Iran, and a part of the local monographs and studies conducted by Iranian writers and intellectuals on villages and faraway rural areas of Iran, the likes of which can be seen in the writings of Al-e-Ahmad, Gholamhossein Saedi, and a few others (books like Orazan, Ahl-e havā, Ilakhchi, Kharg Island, the Unique Pearl of the Persian Gulf, and Tat People of Block-e-Zahra). In O.K. Mister the slogan “Dirt, Flower, Flour” is presented as a way of fending off Western culture and technology, and as a way of “going back to oneself” and the idea of Iranian authenticity.

These films narrate the romantic nostalgia of an Iranian intellectual, the revulsion that he/she feels towards impure urban spaces, his/her escape to the peaceful and pure rural areas, and work as his/her invitation to go back to our roots, to tradition, spirituality, and morality while also being a sign of the collective melancholy of Iranian intellectuals and filmmakers in the 1960s and 1970s.

Sources:

Fitting, Peter. “What Is Utopian Film? An Introductory Taxonomy.” Utopian Studies 4 (2):1 – 17. 1993.

Eslami, Maziar and Farhadpour, Morad, Paris-Tehran, The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami. Rokhdad-e Nou. 2008.

Deleuze, Gilles, Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Continuum International Publishing Group. 2005.

Mirsepassi, Ali. Political Islam, Iran, and the Enlightenment: Philosophies of Hope and Despair, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Freud, Sigmund. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. XXI, London, Hogarth Press, 1961.

Agamben, Giorgio. Stanzas: Word and Phantasm in Western Culture trans. Ronald.L. Martinez, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1993